For reasons ranging from relatively good, to actual malware.

Researchers from

Facebook

and Carnegie Mellon University have published a paper (

PDF

) in which they show that out of a sample of over 3 million secure connections to

Facebook

, 0.2% used a forged SSL certificate.

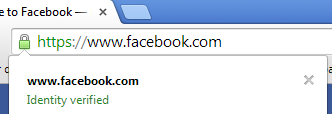

SSL and its successor TLS are encryption protocols that protect many Internet connections, including those using HTTPS, the secure version of HTTP. SSL/TLS does this by doing two things: first, it makes sure the connection is encrypted. Secondly, it allows the client to authenticate the identity of the server.

The second part matters: it means that a connection attempt to a secure server should fail if, for instance because of a malicious DNS configuration, a connection is made to a fake server set up by an attacker. It also prevents man-in-the-middle attacks, where a connection to the real server is ‘broken’ into two encrypted parts by a malicious actor placed somewhere in the middle.

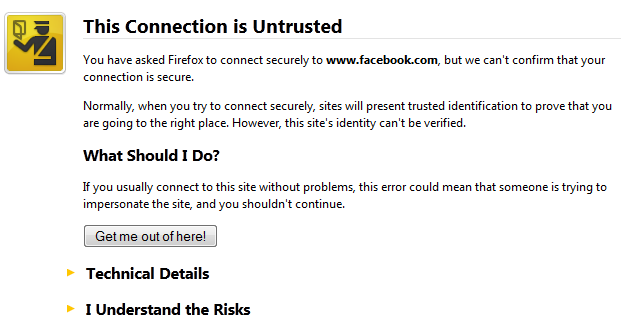

Provided the certificate presented by the other end of the connection is actually forged (and not maliciously obtained from a legitimate certificate authority, as we saw in the case of

DigiNotar

), the client will automatically end the connection. Or, if a human is behind the client, they will be given a clear warning that they should only continue if they know what they’re doing.

From the server’s point of view, it is generally not possible to detect the fact that a client is connecting through a forged certificate. The researchers, however, found a way around this by using a

Shockwave Flash

applet that initiates an SSL/TLS connection, parses the certificate presented by the other end, and sends this result to the real server. They used this to detect any forged certificates being used when clients connected to

Facebook

.

While this didn’t always work – for a number of reasons, out of more than 9 million connections made, a well-formed certificate could be read from only 3.4 million of them – it worked in enough cases for statistics to be performed. The researchers did point out that their detection method can fairly easily be evaded by an attacker who is aware of it.

Out of the 3.4 million certificates, a little under 7,000 (or about 0.2%) turned out

not

to be legitimate. The number may seem small, but it is not insignificant, especially given the sheer volume of HTTPS connections made over the Internet every day.

Not all of these fake certificates are actually malicious: in many cases they were issued by anti-virus software running on the device itself, or by a firewall product running on the gateway. The researchers make the (probably correct) assumption that these certificates were explicitly or implicitly installed by the users and do not consider this to be a problem in itself.

Still, they rightly point out that such certificates could introduce an extra weakness. It is, for instance, possible that the issuer of such a certificate could be compelled to hand over their signing keys to a government. And in the case of

Cyberoam

, all of the company’s appliances used the same private signing key, which could be read by anyone owning such an appliance (an issue which has since been

resolved

).

In some cases, however, the researchers found the forged certificate to be included with a definite malicious purpose. They detected 112 certificates issued by ‘IopFailZeroAccessCreate’, something they could

link

to malware.

The paper makes an interesting read, both for the methodology used and the conclusions it reaches. SSL/TLS works well in almost all cases. But given the billions of supposedly secure connections made on a daily basis, ‘almost all’ isn’t good enough.

Posted on 13 May 2014 by

Martijn Grooten

Leave a Reply