Proposals could cause serious damage to business and the economy, and are unlikely to stop terrorism.

This week, in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks on the French offices of

Charlie Hebdo

magazine, UK prime minister David Cameron

wondered

whether the UK would ‘want to allow a means of communication between people which [it] cannot read’, adding that he certainly wouldn’t want that.

To a non-technical audience, Cameron’s comments probably sound sensible enough. After all, isn’t it awful that people can plan atrocities without the government being able to find out?

Security experts disagree. In fact, they have spoken out with one voice — something of a rare occurrence these days. Graham Cluley

accuses

the prime minister of ‘living in cloud cuckoo land’, while at

Forbes

, Thomas Fox-Brewster

imagines

the UK economy crumbling as a consequence of Cameron’s plans. Across the ocean,

Threatpost

‘s Dennis Fisher

points out

that encryption is not the enemy.

I agree with all of them. I think privacy is a fundamental right, and if we were to give that up because of these truly horrible attacks, then we would be letting the terrorists win. Several stories about intelligence agencies abusing the surveillance powers given to them — for instance to

research

spouses’ behaviour — have strengthened the belief that even if you have nothing to hide, you may still have many things to fear.

But I also realise that the rather abstract notion of privacy is unlikely to be a winning argument. So let’s look at what would happen if Cameron’s proposals were implemented.

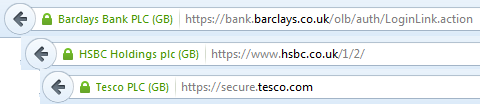

It has been

suggested

that the proposals could cause problems for online banking and online shopping, both of which rely on secure HTTP connections. As long as the banks and the shops are based in the UK, this isn’t a problem though: intelligence or law enforcement agencies can already go to these companies and demand access to certain communications. As long as they have a warrant to do so, and as long as they only ask for what they really need, I have no problem with that.

UK banks and online stores wouldn’t be affected by the proposals.

It is more complicated if the communication happens between individuals — for example because they are using

WhatsApp

, which uses end-to-end encryption, or PGP-encrypted email. It is very possible that such forms of communication could be banned: ISPs can be asked to null route-encrypted emails and apps can be added to a blacklist which already includes apps that display child-abuse images. The UK government might even ask the Spanish government for advice, as it has allegedly

arrested

people for using encrypted email.

This is not the kind of society I would want to live in, and a government introducing these sanctions would receive serious criticism from privacy activists — but it is technically feasible to do so, and it’s probably not something that will affect many people’s lives very much.

Of course, the Internet doesn’t stop at the UK’s borders. What if someone were to make a secure connection to

GMX

in Germany to read their email, to

Yandex

in Russia to search the Internet, or to

Alibaba

in China to conduct business? Or what if someone were to use a VPN to connect to a server in a country with less draconian Internet laws?

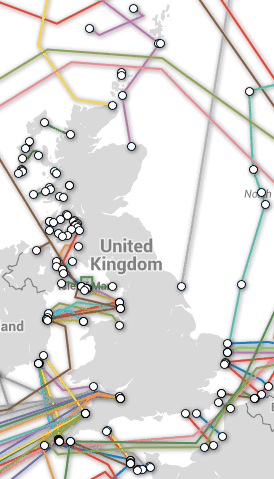

The only way for the government to stop this would be to check at the borders — and although the UK is well connected, it being an island nation, the number of places where Internet leaves the country is fairly limited and it would be entirely possible for the government to intercept the traffic at those points.

Submarine cables through which Internet traffic to and from the UK flows; source:

Submarine Cable Map

.

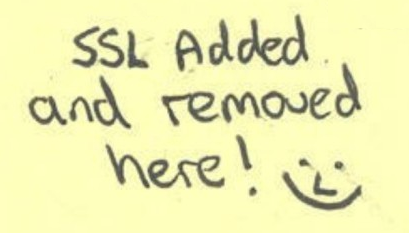

Because the UK is a business-friendly country with a generally well-meaning government, secure connections wouldn’t simply be dropped. Rather, they would be decrypted and then re-encrypted, using a ‘Dave-in-the-middle’ attack (although the government would no doubt find a more euphemistic term for it).

It’s not hard to imagine a publicity campaign explaining to users how to add the special government-approved SSL certificate to their browsers and how to use the government-approved VPN ‘to prevent criminals on the same WiFi network from listening in on your secure conversations’. The highlight of the campaign would be David Cameron personally putting ‘SSL added and removed here’ stickers on the routers where Internet traffic leaves the country.

Of course, this would lead to public outcry.

Or perhaps it wouldn’t — most people’s reactions to the revelations that a lot of their Internet communications were being read by their own government and its friends were pretty mild. It is not beyond the realms of possibility for a government to be able get away with this, as long as it could manage to convince the population that the terrorist threat was very great.

Sure, privacy activists will try hard to circumvent these measures, but as long as a government controls its country’s Internet connections with other countries, the activists will be rather powerless. Many have suggested

steganography

(where secret messages are hidden inside innocent-looking messages) as an answer, but that scales badly and requires the two ends to be able to communicate the protocol in a way that the government couldn’t find out.

However, while most people might accept these measures, albeit grudgingly, businesses will not — and they can easily move their headquarters or offices from the UK to another country where they can communicate securely.

Businesses dislike terrorism as much as everyone else — and as they thrive in stable societies, they have a lot to lose from it — but they would also be extremely concerned about governments reading their communications. They would be justified in being skeptical about claims that this was only being done to prevent terrorism, and that the information wouldn’t be used to the government’s advantage in other ways. Businesses have moved abroad for less serious reasons.

Since the

Patriot Act

was brought in, not having servers in the US has been a selling point for some online service providers. Not having servers in the UK could easily become an even stronger selling point and one that, given the smaller size of the country, would be easier to achieve.

And this is why I agree with Thomas Fox-Brewster that even if you ignore the serious privacy implications, Cameron’s proposals would seriously damage the country’s economic activity — which would likely destabilise the country far more than terrorism could.

But would Cameron’s proposals prevent terrorism? Even if they could, in theory, put a stop to some of the methods terrorists are currently using for their communications, the fact that terrorism is much older than the Internet should make it clear that the only realistic answer to that question is a negative one. It’s also worth noting, as The Grugq

pointed out

, that the

Charlie Hebdo

attackers were brothers. This provided them with a lot of ‘natural OpSec’ that no government could have done anything about.

Posted on 15 January 2015 by

Martijn Grooten

Leave a Reply