We’d better get used to a world where malicious traffic is encrypted too.

According to some people, myself included,

Let’s Encrypt

was one of the best things that happened to the Internet in 2015. Now that, as of December, the service is in public beta, anyone can register certificates for domains they own, in a process that is both easy and free.

Cybercriminals have noticed this too, and rather unsurprisingly,

Trend Micro

reports

that a certificate issued by

Let’s Encrypt

was used in an Angler exploit kit-powered malvertising campaign, to make the malicious advertisements harder to detect.

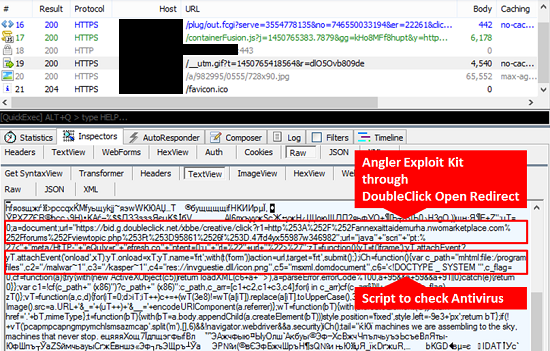

The malvertising taking place. Source: Trend Micro.

What makes this case particularly interesting is the fact that the domain for which the certificate was issued was the subdomain of a legitimate site, whose DNS was compromised. As domain-based reputation isn’t usually granular enough to distinguish between subdomains, this could have helped them avoid detection even further.

Let’s Encrypt

only issues Domain Validation certificates, which don’t do more than validate the domain; hence it doesn’t

believe

it needs to police the content of the domains for which it issues certificates, although as a possibly temporary compromise, the domains are checked against

Google

‘s

Safe Browsing API

before a certificate is issued.

I agree with

Let’s Encrypt

here. I think our goal should be to encrypt all Internet traffic, and if bad traffic gets encrypted too, then that is a feature of the system, not a bug. Given how easy it is to register certificates, more policing would simply lead to a cat-and-mouse game. And there is also the danger of a slippery slope, where governments and interest groups start to pressure

Let’s Encrypt

to revoke the certificates of sites they perceive as bad.

We’ll just have to accept that more and more traffic is encrypted and find ways to block malicious activity in an environment where all traffic is encrypted.

Of course, this particular case is a little different: the exploit kit users in this case didn’t “own” the subdomain; they were merely able to point it to their own server. It might be worth

Let’s Encrypt

considering an automatic way in which domain owners can revoke certificates issued to subdomains. But that may well complicate the whole process and make little impact in practice. After all, for a successful malware campaign, domains only need to be active for a very short period of time.

If you’ve been telling people that the mere presence of a ‘lock icon’ in the address bar is a sign that a site is harmless, now is really the time to stop doing that.

Posted on 08 January 2016 by

Martijn Grooten

Leave a Reply