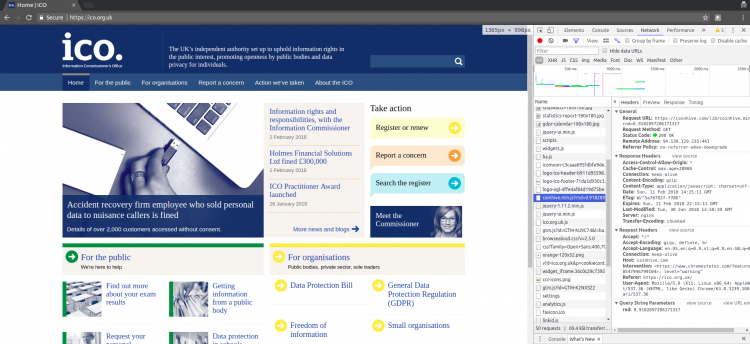

This was awkward. On Sunday, the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), the UK’s data protection regulator and thus the public body that issues fines for data breaches, was found to be serving a JavaScript-based cryptocurrency miner on its website.

The issue was first

reported

by security researcher Scott Helme, who discovered that the ICO wasn’t the only organisation affected: thousands of sites, including many government sites in a number of countries, were serving the same JavaScript code. The source of the issue was quickly determined to be a piece of third-party code used to improve a website’s accessibility for the visually impaired.

The technique used wasn’t particularly advanced: some mildly obfuscated code had been added that loaded the miner from

Coinhive

, a site used in many such attacks. In fact, the same

Coinhive

account

had been used

against some other websites a few days earlier.

TextHelp

, the company that was serving the code,

took

the affected web server offline after about four hours.

The current value of most cryptocurrencies makes this an attractive way for cybercriminals to make money, but as attacks go, it is barely more harmful than inserting a

silly

YouTube

video

into the web page. But while we consider all the other things that could have happened (such as form data being stolen, or an exploit kit being served) it is worth noting that there are important lessons to be learned from this hack.

The first is that there are actually ways in which content can be loaded from third-party sites that significantly reduce the harm. In particular, by setting the

Content Security Policy

(CSP) header, a site can inform a browser that only content from specific domains is allowed to be included. Using

Subresource Integrity

(SRI) can even allow only JavaScript code with a specific cryptographic hash to be included, though that is probably most useful in cases where the third-party site is controlled by the same organisation.

The second lesson is that a company like

TextHelp

can make it easy for researchers to find a security contact to report issues like these. This is where the recently introduced

security.txt

standard becomes very useful: it is a simple text file hosted at a predictable location on a website, where the site owner can put their security contacts, as well as various security policies. Both

Facebook

and

Google

have adopted the standard, but it is probably most useful for smaller companies and organisations that don’t have a large and visible security team.

This morning,

Virus Bulletin

added a security.txt file to its website.

Leave a Reply