Just because it won’t be exploited, doesn’t mean you shouldn’t patch it.

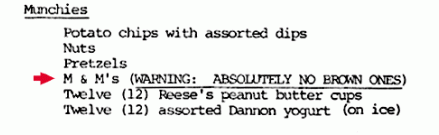

There is a famous story about the rock band Van Halen whose lists of requirements when performing a show included some

M&Ms

— but “absolutely no brown ones”.

The story is

true

and has little to do with childish rock star behaviour. The band’s technical requirements were so complicated that they were worried the concert organisers wouldn’t read them all. The

M&Ms

requirement, stuck in the middle of the long rider, provided the band with a quick check to verify whether it had actually been read in full detail.

From Van Halen’s rider. Source:

The Smoking Gun

The world of security is full of brown

M&Ms

requirements: vulnerabilities that one needs to patch, not so much because there is an actual risk, but to show one has a proper patching policy.

POODLE, which I

wrote about

last autumn, is a good example of this.

The vulnerability exists in SSLv3 (though a

related vulnerability

was later found to affect TLS 1.0-1.2), an older version of the SSL/TLS protocol that was still supported by many web clients and servers. Crucially, someone in a man-in-the-middle position was able to downgrade an HTTPS connection to use SSLv3 and then perform the POODLE attack.

Doing this would let them gradually reconstruct bytes of the encrypted HTTPS request that are located in a predictable position. Most typically, these are session cookies.

To perform the attack, an attacker needs to be able to run some (JavaScript) code in the target’s browser, which they can do by injecting the code into an unencrypted HTTP response received from the Internet.

Being able to hijack a browsing session is bad, but the harm one can do is fairly limited. In the worst-case scenario — that of an online banking session — one may be able to view online banking statements, but is unlikely that one could use this to transfer money out of the account. If that is possible, the bank has far bigger problems than POODLE to deal with.

Moreover, man-in-the-middle attacks scale badly, making this a very unattractive attack. It is no wonder that there have been no instances (that I know of) of POODLE being exploited in the wild.

So when

The Register

reported

that a number of banks (including

Barclays

,

Halifax

and

Tesco

) are still vulnerable to POODLE, it isn’t too big a deal in itself.

But just as the presence of brown

M&Ms

may be indicative of a larger problem, the fact that those sites are vulnerable to POODLE makes one wonder how well their administrators patch other vulnerabilities — ones that

do

matter. Will those banks be vulnerable to the next Heartbleed?

And of course, there is always a chance that someone will find a much more serious way of exploiting POODLE, just as there is always a chance that a food allergy is the reason behind the odd the brown

M&Ms

requirement. Which is another reason one shouldn’t take risks.

Security in general, and patching in particular, is a process. Patches should, of course, be tested properly, but the aim should always be to apply the patch. Making a decision based on the calculated risk of exploitation is rarely, if ever, a good idea.

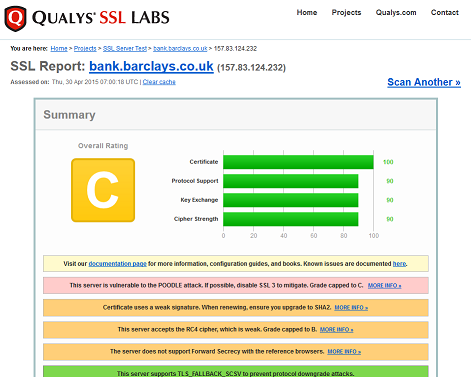

Qualys

SSL Labs

is an easy way to see how well websites have patched against weaknesses that matter and those that don’t matter too much.

On the subject of online banking security, a far bigger worry is the fact that many banks (including the three mentioned above) don’t use HTTPS by default on their main page. As this is where many people find links to their online banking site, this is an actual problem: it wouldn’t be hard for an attacker with a man-in-the-middle (or man-in-the browser) position to modify this link. And no SSL checker will inform you of that.

Posted on 30 April 2015 by

Martijn Grooten

Leave a Reply