Users easily tricked, but plenty of opportunity for the malware to be blocked.

Researchers at

Trend Micro

report

that the ‘Vawtrak’ banking trojan now also spreads through

Office

macros, embedded in documents that are attached to spam emails.

Vawtrak rose to prominence late last year, when it broadened its scope from targeting Japanese banking users (only) to targeting users from banks in many other countries, leading to

suggestions

that it posed a challenge to Zeus for the title of ‘king of botnets’. Last month, we published a

thorough analysis

of the malware by

Fortinet

researcher Raul Alvarez.

Last year, cybercriminals

rediscovered

the use of

Office

macros to spread malware. Prevalent in the late 1990s, macro viruses disappeared quickly when newer versions of

Microsoft Office

had macros disabled by default. However, malware authors have recently started to use social engineering to trick users into enabling macros, thus allowing the malicious code to be executed.

Sophos

researcher Gabor Szappanos was one of the first to notice the resurgence of macro malware; he wrote an

article

for

Virus Bulletin

on the subject in July last year. Since then, the use of macros by malware has

continued to increase

.

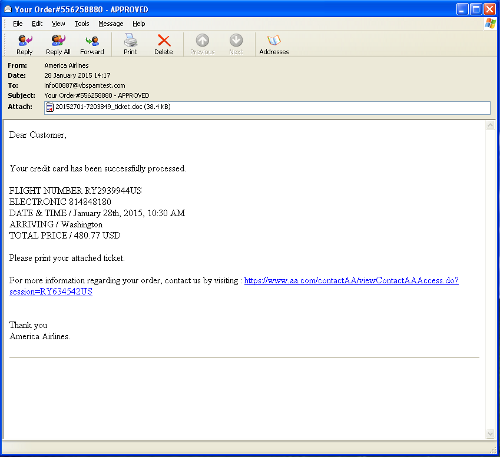

It wasn’t difficult to find an example of a spam email carrying such a macro in our

VBSpam

archive. The email in question has been sent in January and claimed to contain an

American Airlines

ticket. (Incidentally, the same email and the same attachment were

analysed

by the

Security by Ojscurity

blog, which explains in detail how to analyse the malware from the

Linux

command line.)

The mildly obfuscated VBScript code generates a PowerShell script that downloads the file ‘update.exe’ from a server that has since been taken down. This executable would then download Vawtrak (though it’s worth noting that it could also be used to download other kinds of malware).

It is often said that attackers have an easy time: they only need to find one vulnerability to exploit — be it an unpatched piece of software, a piece of security software failing to do its job properly, or a person being tricked into doing something they shouldn’t do. This may be true, but in this example we see that they also have many hurdles to overcome in order for their attack to be successful.

First, the spam needs to bypass spam filters (the email we found was blocked in real time by all solutions that were on the

VBSpam

test bench at the time). Then the user needs to open the email and open the attachment — which must not trigger anti-virus software. The user must then be convinced to enable macros (an option they may not even have if they work in a corporate environment).

The PowerShell script then needs to download the malware over an HTTP connection, and this malware needs to download the Vawtrak sample. In both cases, web security software could block the download, anti-virus software could block the executable, and the server could have been taken down already.

Finally, as Raul Alvarez’s paper showed, Vawtrak itself consists of multiple layers. The executable generated by each of these layers could be blocked, or it could be prevented from making changes to the registry and thus maintaining persistence on the machine.

Malware is a serious problem and we’re doing okay (at best) at fighting it. But picking on one of many defence layers to

show how poorly we’re doing

, as happens regularly, isn’t helpful — and ignores the many opportunities there are to stop malware from executing.

Posted on 24 February 2015 by

Martijn Grooten

Leave a Reply