Large organisations working in national security and international affairs run highest risk.

Anyone can be a target of cybercriminal attacks these days. But some are bigger targets than others.

You don’t have to be a rocket scientist to understand that rocket scientists are more likely to be subject to targeted attacks than retirees who only access the Internet to browse

Facebook

. But what factors increase the likelihood of someone becoming a target?

A new paper (

pdf

), to be presented at the

Financial Cryptography and Data Security 2015

conference next week, attempts to answer that question. In particular, the authors look at what factors contribute to organisations and individuals being more (or less) likely than average to be subject to email-based targeted attacks (spear phishing).

The authors (Olivier Thonnard, Leyla Bilge, Anand Kashyap and Martin Lee – all current or former

Symantec

employees) were inspired by epidemiology, which is the study of the patterns, causes and effects of diseases. Like any serious paper on epidemiology, their paper makes ample use of statistics to determine the statistical relevance of their findings.

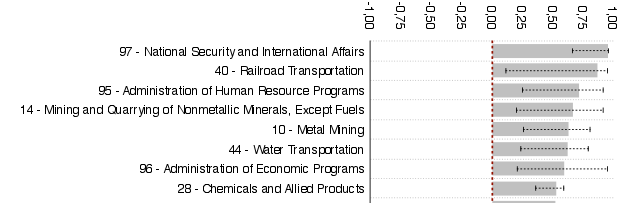

Perhaps unsurprisingly, organisations working in national security and international affairs run the highest risk of being targeted, with mining and railroad companies also near the top of the table – though in the latter case, the confidence interval is rather large. Even less surprising is the fact that size matters: the larger your organisation, the more likely you are to become a target.

SIC

codes of industry sectors that are most likely to be subjected to a targeted attack.

For the individuals being targeted, both their job title and their seniority level matter in ways that aren’t too surprising, though I thought it interesting to see that support staff are even more likely to be targeted than managers and directors.

An individual’s location is relevant too (Australia, the UK and France top the table, with individuals based in the US actually less likely to become a target), as is the number of

LinkedIn

connections they have (the more connections someone has, the more likely they are to become a target, except when the number of connections exceeds 500). In both cases, it is important to note that correlation doesn’t equal causation: moving to India and disabling your

LinkedIn

account will probably not make you any less of a target.

A shorter follow-up study confirmed that the results from the paper work well as predictors for future attacks.

Studies like this could help determine premiums in the growing market of

cyber insurance

. In some cases, they could also help determine the level of security needed for a certain organisation.

Of course, for an intern working in sales on a small farm in India, who doesn’t have a

LinkedIn

profile, it is good to keep in mind that most attacks on the Internet aren’t targeted – but they can still do a lot of harm.

Martin Lee, one of the authors, has previously carried out a similar study focusing on academic recipients, the results of which were presented at

VB2012

in Dallas. You can download a pdf of Martin’s paper

here

.

Posted on 21 January 2015 by

Martijn Grooten

Leave a Reply