Many devices simply waiting for router advertisements, good or evil.

When early last year I was doing research for an

article

on IPv6 and security, I was surprised to learn how easy it was to set up an IPv6 tunnel into an IPv4-only environment. I expected this could easily be used in various nefarious ways.

I was reminded of this when I read about a DEFCON

presentation

on using IPv6 to perform a man-in-the-middle attack on an IPv4-connected machine.

I did not attend DEFCON, but the presenters Brent Bandelgar and Scott Behrens provided details in a

blog post

for their company

Neohapsis

as well as in their presentation

slides

. Moreover, they

shared the source code

of the tool they developed on

Github

.

The attack refines the proof of concept of an attack possibility

described in 2011

, by making it also work against

Windows 8

and providing a

bash

script that is supposed to work out-of-the-box. This script will no doubt be popular among penetration testers, but also shows possibilities for those with malicious motives.

For me, the script didn’t work right away, but some minor tweaks got it working, after which the traffic from my wife’s

Windows 7

laptop was flowing through my virtual

Ubuntu

server. And while I didn’t even attempt to read the traffic generated by this ‘husband-in-the-middle’ attack, I could have done. I could also have performed a similar attack in a local

Starbucks

.

The attack makes use of the fact that all modern operating systems support both IPv4 and IPv6 connections. This in itself is a good thing for the migration towards IPv6, as is the fact that the IPv6 connection, if available, takes precedence.

Moreover, operating systems such as

Windows 7

and

8

have DHCPv6, the IPv6-version of DHCP, enabled by default. This means that if they haven’t already got an IPv6 connection, they will obtain one from any DHCPv6 server running on the local network.

This is what the

Neohapsis

researchers do to get machines to connect to their device. As this merely allows them to capture IPv6 traffic in a IPv4-only network, they then use a protocol called

NAT64

to allow their server to route this traffic to the IPv4-Internet.

NAT64 is one of several protocols used to make the migration towards IPv6 easier: it allows IPv6-only networks to connect to IPv4-only services on the Internet.

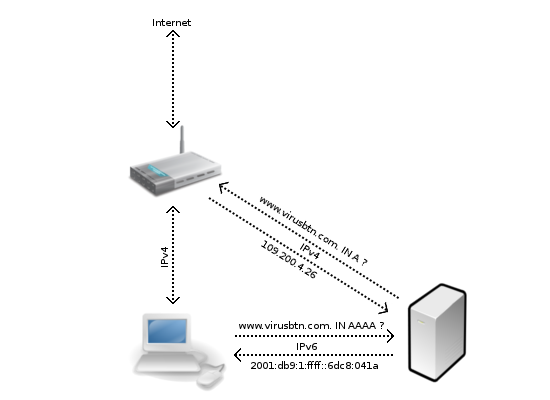

NAT64 in a rogue set-up, with the NAT64 server on the right.

It works by setting up a DNS server that returns IPv6 addresses in which the IPv4 address is embedded. If a request is made for the AAAA record (IPv6 address) of a domain, the response will be an address in some predefined

/96

IPv6 subnet – that is, a subnet in which all but the final 32 bits are fixed. These 32 bits will be the A record (IPv4 address) for the same domain.

Say, for example, the subnet is

2001:db9:1:ffff::/96

and a request is made for

www.virusbtn.com

, then the response will be

2001:db9:1:ffff::

6dc8:041a

. Indeed,

6dc8:041a

is the hexadecimal representation of

109.200.4.26

, the IPv4 address of

www.virusbtn.com

.

Requests to this IPv6 address will then be routed through the server running NAT64 – in this case, the server set up by the attackers. They are thus able to see all traffic from the now IPv6-connected machine, except that in which the IP address is hard-coded.

Of course, in principle this means they can only read traffic that isn’t encrypted, but that still allows for many possible attacks with serious consequences. At the same time, the fact that the intercepting device runs on the same local network might make performing cryptographic timing attacks such as

Lucky Thirteen

easier.

To see the possibilities for malware that is able to intercept all traffic, one just needs to look at a 2011 variant of the TDSS rootkit which

set up its own IPv4 DHCP server

. In that case, however, the malware had to compete with the real DHCP server, while in this case the fact that IPv6 always takes precedence over IPv4 means there is no such competition.

The simplest way to fend off this kind of attack is to turn off IPv6 on devices that do not need it. This will, of course, hinder the migration towards IPv6 and may not be an option for transportable devices, as these may sometimes find themselves in an environment where IPv6 connectivity is needed.

The researchers also mention

RFC6105

, an informational document published by the

IETF

on how to deal with rogue router advertisements, as a possible defence strategy.

But ultimately, the best way to defend against these kinds of attacks will be to make sure the device always has an IPv6 connection. Attacks such as this one will not work on devices that are already IPv6-connected.

Posted on 12 August 2013 by

Martijn Grooten

Leave a Reply